The stars move with our seasons. For most of us, some move below the horizon and we lose sight of them for part of the year. But the circumpolar stars stay above the horizon all hours of the day, every day of the year. They are there now, even if it is daylight as you read this, they are there. there’s not a lot you can count on here on Earth – or even in the heavens – but you can count on them.

The Big Dipper asterism is the best known of the circumpolar groups at all latitudes north of 41 degrees north latitude. (That is the northern half of the mainland United States and most of Europe.)

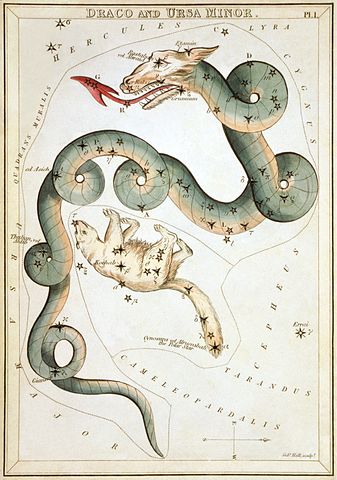

The Big Dipper is part of a bigger constellation, Ursa Major or the Great Bear.

In Greek mythology, the god Zeus had fallen in love with the maiden Callisto. In a story that would make the news today, and get Zeus some bad headlines, Zeus got her pregnant. Callisto was a nymph in the retinue of the goddess Artemis. But she would not be with anyone but Artemis. Zeus disguised himself as Artemis and seduced Callisto. When the child Arcas was born, Zeus’ wife Hera turned Callisto into a bear in revenge.

Callisto wandered the forest for years in bear form, until a chance meeting with her son, Arcas. He was the king of Arcadia and a great hunter. He raised his spear to strike at the bear, not knowing it was his mother. Zeus stepped in and sent them up to the heavens with Callisto as the Great Bear and Arcas as Bootes the Herdsman. (Or maybe he is Ursa Minor, the Little Bear, depending on whose mythology you follow.) Hera was not pleased that Zeus stepped in, so she wever, and conspired with the gods of the sea so that the Bear could never swim in the ocean. That is one explanation – totally unscientific – for why Ursa Major never sets

Where are you? If you’re with me in the Northern Hemisphere, every star north of the celestial equator is circumpolar, and every star south of the celestial equator is below the horizon. At the Earth’s South Pole, every star south of the celestial equator is circumpolar, whereas every star north of the celestial equator remains beneath the horizon.

And at the Earth’s equator, no star is circumpolar because all the stars rise and set daily in that part of the world. You can actually see every star in the night sky over the course of one year.