My friend Patricia, who spends part of the year in Florence Italy, had a conversation with me and Dante came up. By coincidence my college copy of Dante was sitting on the desk next to me and I told her that I had found it on a shelf when I was sorting out books to give away. I started looking through it, and besides all my marginalia, I found scraps of paper with diagrams and notes, including a few from my professor from the course that had me reading the book.

I am in my almost-annual rereading of Moby-Dick at the pace of a chapter a day, and Pat said that that was the way she had read Dante. I found Dante to be much more difficult than Melville. Even though I do love poetry, his terza rima is too repetitious and the language only made sense because I was reading it with a guide.

Actually, any epic poem I have read or tried to read has piqued my short attention span. I failed with Gilgamesh, Odyssey and Iliad, Aeneid, Beowulf, the Nibelungenlied, and Paradise Lost, Even some modern epic poems seem to be beyond me – Walcott’s Omeros, even the more modern Paterson by William Carlos Williams, and Pound’s Cantos.

With Dante, one translator, Robert M. Durling, has done prose translations of Dante that drop the meter and rhyme that trouble readers like me. Turning verse to prose seems like cheating, but then again any English translation is flawed. Durling says, “…the closely literal style is a conscious effort to convey in part the nature of Dante’s Italian, notoriously craggy and difficult even for Italians.”

Dante Alighieri was born in 1265 in Florence. His family, of minor nobility, was not wealthy nor especially distinguished. His mother died when he was a child, and his father before 1283. At about the age of 20 he married Gemma Donati, by whom he had three children.

We don’t know much about his formal education. Probably he studied with the Dominicans, the Augustinians, and the Franciscans in Florence, and for a time at the university in Bologna.

In 1295 he went into politics and in 1300 he became one of the six governing Priors of Florence. In 1301, the political situation forced Dante and his party into exile. For the rest of his life, he wandered through Italy, perhaps studying in Paris, and depended on the generosity of various nobles. He continued to write and at some point late in life, he took asylum in Ravenna where he completed the Divine Commedia. For that, he was much honored at his death in 1321.

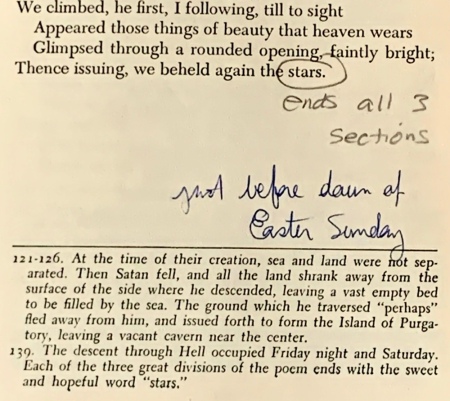

My Moby-Dick reading will take me into May since I began on Christmas Day because that was when Ishmael’s Pequod set sail. The Divine Comedy begins in a shadowed forest on Good Friday in the year 1300. If I was to walk with Dante again on Good Friday (which is always the Friday before Easter Sunday) that would start me reading on March 29. Sailing on the Pequod and walking through the Inferno, Purgatorio and Paradiso would probably be too much all at once.

The Divine Comedy has three sections, or canticles, Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso. Technically there are 33 cantos in each canticle and one additional canto, contained in the Inferno, which serves as an introduction to the entire poem. So many days…

I looked for Dante things in the library and found Prue Shaw, one of the authorities on Dante. Reading Dante: From Here to Eternity is her introduction to his poem. which is sometimes considered the greatest literary work of all time and not simply a medieval treatise on morality and religion.

Maybe I need a guide through those three places with their complicated geography through the afterlife. Surely I need a guide to thirteenth-century Florence and the people and places that influenced him. After all, Dante had a guide. Beatrice serves as the pilgrim’s bridge to salvation. She is a descends into hell to call upon Virgil for his help and to instruct him to lead the pilgrim Dante on an otherworldly journey.

I was required to read some Dante in college and I even included The Divine Comedy in a major paper I wrote for an undergraduate independent study. I know I made it through Inferno, with some skimming I am sure. Purgatorio was different. While I was relieved to be out of the depths of the abyss of Hell and heading skywards on the titular mountain, I didn’t feel relieved.

Having been raised Catholic but having lost most of my beliefs in college, (according to my mother, because I took religion courses) Purgatory always seemed like a terrible place. Dante puts Mount Purgatorio somewhere in the Southern Hemisphere, which I found amusing. There are contained all the struggles and temptations that humankind must overcome if they are to attain Paradise.

The Inferno’s plunging concentric circles are reversed in Purgatorio’s sseven terraces, built one on top of the other and each associated with another level of Deadly Sin.

Having made it through Hell and taken a cable car up Mount Purgatorio, I entered – without my own Beatrice – Paradise. Dante’s experiences in the Inferno and Purgatorio were arduous and harrowing, but this third part is a journey of comfort, revelation, and, above all, love – both romantic and divine.

The third part should have been the most enjoyable to read but I, like most readers, focused on that inferno of Hell.

I may dip back into Dante after Ishmael gets picked up floating in the ocean clinging to a coffin. Perhaps, I will take my copy to my local coffee shop and read a little each time. Can I conjure up Dante, or better yet, Beatrice, to guide me?

The two illustrations of Dante used here are ones I created using AI.